Richard Rich was born in London about the year 1496, and as a boy he was intimate with Sir Thomas More, who, when he was on trial through Rich's treachery, said, 'Of no small while I have been acquainted with you and your conversation, who have known you from your youth hitherto. The title was created in 1547 for Sir Richard Rich who was made Baron Rich, of Leez. Rich was a prominent lawyer and politician, who served as Solicitor General and Speaker of the House of Commons and was Lord Chancellor of England from 1547 to 1551. The Rich family descended from Richard Rich, a wealthy mercer who served as Sheriff of London in 1441, and Sir Richard was his great-grandson.

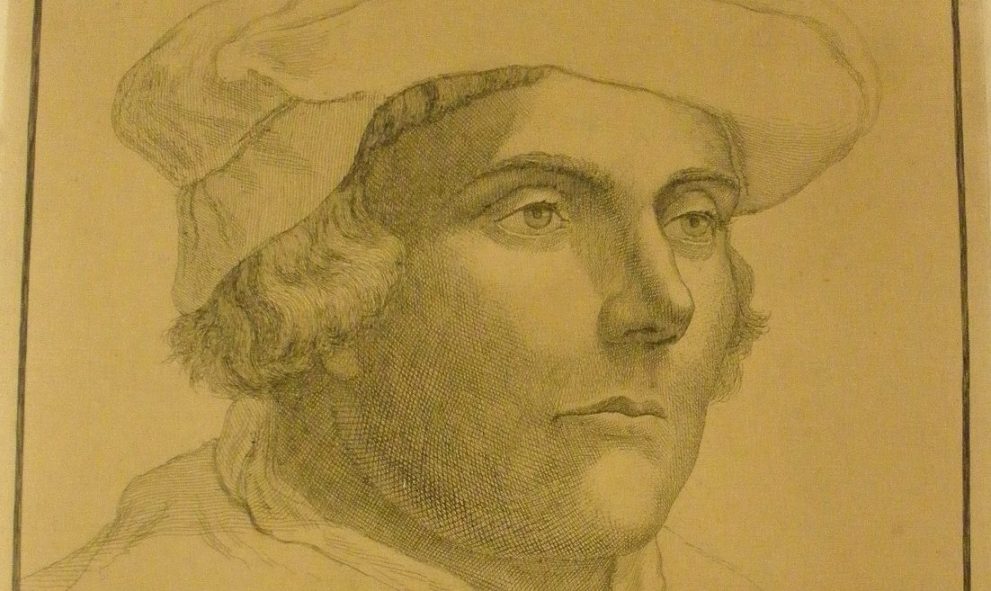

| Sketch of Rich by Holbein Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons |

Little is known about Rich's early life. We're not even certain of his parents. They may have been Richard Rich and his wife, Joan Dingley. Or they could have been John Rich and Agnes - her family name is unknown. He was born around 1496 or 1497 because a document from 1551 says that he was fifty-four years old 'and more.'

He studied law; tradition has it that he studied at Cambridge, and at one time, vied unsuccessfully to be chancellor of the university. He was an acquaintance of Thomas More, as they were members of the same parish.

His career began as a commissioner of the peace in Hertfordshire, and he held a variety of positions on his climb to power. He became a member of Parliament in 1529 and in 1533, Rich was made the solicitor general - what Americans would call the 'attorney general.'He worked for the king in establishing the royal supremacy and the Act of Succession.

Rich was very skilled in figuring out how to get the king what he wanted, by any means necessary. Thomas More spoke of what Rich's reputation had been, even before he took the position of solicitor general:

'You know that I have been acquainted with your manner of life and conversation a long space, even from your youth to this time; for we dwelt long together in one parish, where, as yourself can well tell (I am sorry you compel me to speak it), you were always esteemed very light of your tongue, a great dicer and gamester, and not of any commendable fame either there or at your house in the Temple, where hath been your bringing up.'

When Bishop Fisher was arrested for denying the royal supremacy, Rich visited him in the Tower and coaxed Fisher into revealing his opinions on the matter, swearing the only person he would tell about it would be the king. Rich lied. He used Fisher's statements to convict him, and the outraged, betrayed Fisher denounced Rich in court for it.

When Bishop Fisher was arrested for denying the royal supremacy, Rich visited him in the Tower and coaxed Fisher into revealing his opinions on the matter, swearing the only person he would tell about it would be the king. Rich lied. He used Fisher's statements to convict him, and the outraged, betrayed Fisher denounced Rich in court for it.Mr. Rich, I cannot but marvel to hear you come in and bear witness against me of these words, knowing in what secret manner you came to me. [...] To that he told me that the king willed him to assure me on his honour, and on the word of a king, that whatsoever I should say unto him by this his secret messenger, I should abide no danger nor peril for it; neither that any advantage should be taken against me for the same, no, although my words were never so directly against the statute, seeing it was but a declaration of my mind secretly to him, as to his own person. And for the messenger himself, he gave me his faithful promise that he would never utter my words in this matter to any man living, but to the king alone.

| Thomas More, by Holbein Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons |

More denounced Rich as a perjurer and as a man untrustworthy of any confidence.

'[I]n good faith, Mr. Rich, I am more sorry for your perjury than mine own peril; and know you that neither I nor any one else to my knowledge ever took you to be a man of such credit as either I or any other could vouchsafe to communicate with you in any matter of importance.'

Burn!

| Beautiful, eh? Henry, around 1536, by Holbein |

In 1536, the year of Anne Boleyn's execution, Rich gave a speech at the opening of Parliament in which he compared the king to Solomon for his wisdom, and Absalom for his beauty, and compared the king's love for his subjects to the sun's benevolent rays warming the earth, and driving away the noxious vapors. Rich apparently liked to lay it on thick.

Rich busied himself with dissolving the monasteries when not occupied by his legal duties. He became enormously wealthy, and admittedly, he did use some of that wealth to found a school and an almshouse (poorhouse.) But his terrible reputation remained. The rebels of the Pilgrimage of Grace demanded his removal from office

'...as a man of low birth and small reputation, a subverter of the good laws of the realm, a maintainer and inventor of heretics, and one who imposed taxes for his own advantage.'

| Elizabeth Jenks, Lady Rich, by Holbein Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons |

Speaking of wills, when Katharine of Aragon died, Henry was in a quandary. She had made a will, distributing her property; he wanted her assets for himself. If she was his wife, her will had no legal force and he could simply ignore it. But if she wasn't his wife - as Henry had insisted for about ten years - she had the legal right to dispose of her own property as she saw fit. Richard Rich stepped in to save the day, finding a nice legal loophole to allow Henry to claim her estate without having to admit to being her husband in the process. Rich even helped out by making a complete inventory of her possessions.

In 1539, Rich was appointed as a Groom of the Privy Chamber for the new queen, Anna von Kleefes, and was sent to greet her when she landed in England. But the king was very unhappy with his new wife, and the brunt of his displeasure fell on Cromwell, who had arranged the union. Cromwell had been a mentor and friend to Rich, who now turned around and acted as the chief witness against him.

He zealously prosecuted those who denied the supremacy, including the famous martyr Anne Askew, who wrote that Rich had tortured her with his own hands. As a woman of gentle birth, Askew should have been exempt from such tactics, but Rich was never one to let the law get in his way. He knew how bendable the law was, after all, having made a career of doing so. He was trying to get information from her about Kateryn Parr that could be used to destroy Henry's last queen. Though he could break Askew's body, he couldn't break her silence. Anne Askew went to the stake, her body so broken she unable walk or stand, but having never betrayed her friends.

He was the executor of Henry's will when the king died - a will of questionable authenticity. It is believed by some that Henry's will was never signed by him. It was instead signed with a wooden stamp and the depressions it made in the parchment inked in.

Rich continued his career after Henry died, through the reign of his son Edward VI. Edward's reign was a mire of quicksand alliances shifting by the moment. A story of Rich's political machinations from that time has been preserved. It's one time he gambled and lost.

An event, however, occurred on the 21st December following (1551) which relieved him of carrying forward this unpleasant business, for on that day he surrendered his chancellorship. The Duke of Somerset was at that time in the Tower, and it is said that, though he was there through Rich's instrumentality, Rich now wished to befriend the late Protector and wrote him a letter warning him of something designed against him by the Privy Council. Being in haste, he addressed the letter merely 'To the Duke'. His servant, fancying it was for the Duke of Norfolk, carried it to that duke. He, to make Northumberland his friend, sent the letter to him. Rich, realizing the mistake, and to prevent the discovery, went immediately to the king, feigned illness, and desired to be discharged, and upon that took to his bed at St. Bartholomew's, whither Lord Winchester, the Duke of Northumberland, and Lord D'Arcy repaired, and there they took the surrender of the Great Seal. It is assumed that Rich took this measure to save his neck, and if so he was successful.

When Edward died, he left the throne to his protestant cousin, Lady Jane Grey. Edward had no legal authority to do so; the succession had been enshrined by his father in an act of Parliament. Rich signed a document of the council declaring Mary a bastard and Lady Jane queen, but high-tailed it from court down to Mary's side, where he declared her queen. Despite the fact Rich had been one of the men sent to harass Mary by both her father and her brother, Mary kept Rich in her employ.

During most of Mary's reign, he remained in Essex, vigorously prosecuting protestants, and helped restore some of the very monasteries he had dismantled. Unfortunately for him, it meant giving back some of the monastic properties he had purchased from the crown, and he was never fully compensated for them.

| Tomb of Richard Rich Image courtesy of FindAGrave |

He died in June, 1567 and was buried almost a month later in Felstead. His tomb shows his effigy reclining, reading a book. On it is inscribed his ironic motto: Garde la foy. Keep the Faith.

Sir Richard Richardson Paintings

In 2006, he was voted one of the ten 'Worst Britons' of the last thousand years.

Richard Rich, the son of John and Agnes Rich, was born in Basingstoke in about 1496. It is believed that he studied at Cambridge University before entering the Middle Temple in February 1516.

In 1528 Rich wrote to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey with his suggestions to reform the common law. Later that year he was appointed to the commission of the peace for Essex and Hertfordshire. During this period he became friends with Thomas Audley, the speaker of the House of Commons. In 1529 Rich was elected to represent Colchester.

Rich was appointed attorney-general for Wales on 13th May 1532. The following year Audley, now the Lord Chancellor, arranged for him to become solicitor-general. In this post he helped draft legislation in the House of Lords. (1)

In March 1534 Pope Clement VII announced that Henry's marriage to Anne Boleyn was invalid. Henry reacted by declaring that the Pope no longer had authority in England. In November 1534, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy. This gave Henry the title of the 'Supreme head of the Church of England'. A Treason Act was also passed that made it an offence to attempt by any means, including writing and speaking, to accuse the King and his heirs of heresy or tyranny. All subjects were ordered to take an oath accepting this. (2)

Richard Rich & Thomas More

Sir Thomas More and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, refused to take the oath and were imprisoned in the Tower of London. More was summoned before Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell at Lambeth Palace. More was happy to swear that the children of Anne Boleyn could succeed to the throne, but he could not declare on oath that all the previous Acts of Parliament had been valid. He could not deny the authority of the pope 'without the jeoparding of my soul to perpetual damnation.' (3)

Richard Rich was responsible for the prosecution of More and Fisher and other opponents of the royal supremacy. 'He (Rich) participated in the examination of Fisher in the Tower of London in May 1535, having been sent to ascertain the bishop's opinion of the royal supremacy but promising him to divulge his views only to the king. Fisher's answers furnished the necessary evidence for his conviction of treason.... However, the sources recounting Rich's dealings with More are invariably hostile to him because they were written by members of More's family, their descendants, and Catholic apologists.' (4)

In May 1535, Pope Paul III created Bishop John Fisher a Cardinal. This infuriated Henry VIII and he ordered him to be executed on 22nd June at the age of seventy-six. A shocked public blamed Queen Anne for his death, and it was partly for this reason that news of the stillbirth of her child was suppressed as people might have seen this as a sign of God's will. Anne herself suffered pangs of conscience on the day of Fisher's execution and attended a mass for the 'repose of his soul'. (5)

The trial of Sir Thomas More was held in Westminster Hall and began on 1st July. Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley presided over the case. Unlike Bishop Fisher, More denied that he had ever said that the king was not Head of the Church, but claimed that he had always refused to answer the question, and that silence could never constitute an act of high treason. The prosecution argued that silence implied consent. As Jasper Ridley, the author of The Statesman and the Fanatic (1982) has pointed out, 'while Fisher and the Carthusians, when facing their judges, took their stand for the Papal Supremacy, More rested his defence on a legal quibble'. (6)

It was difficult for the prosecution to maintain that anything that More had said or done constituted a malicious denial of the king's title as Supreme Head. Richard Rich gave evidence that caused Thomas More considerable problems. Rich recalled a conversation that he had with More on 12th June, 1532, when he visited him in the Tower of London. According to P. R. N. Carter: 'The two lawyers engaged in a hypothetical discussion of the power of parliament to make the king supreme head of the church.... and Rich testified (falsely) that during their conversation the former lord chancellor had explicitly denied the supremacy. The alternative view is that More relaxed somewhat during the interrogation by Rich in what was a bit of professional jousting, but that Rich did not see or report this as something new. However, someone, possibly Cromwell, saw that More's statements could be used to convict him of denying the royal supremacy. Hence Rich's evidence was not dishonest, merely used in a way he never foresaw.' (7)

Thomas More denied that he had said any such thing, 'making the valid point that since he had refrained from saying anything so incriminating in the course of interrogations, he was unlikely to have made such an observation in the course of casual conservation'. (8) The court chose to believe Rich and More was convicted of treason. Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley 'passed sentence of death - the full sentence required by law, that More was to be hanged, cut down while still living, castrated, his entrails cut out and burned before his eyes, and then beheaded. Henry VIII commuted the sentence to death by the headsman's axe and he was executed on 6th July, 1535. (9)

It has been argued that it was Rich's evidence that resulted in the conviction and execution of More. 'His alleged perjury received its full reward: on 27 July 1535 Rich was named chirographer of the court of common pleas, but at the cost of his historical reputation.... The fiscal and legal consequences of the Henrician reformation soon brought Rich fresh responsibilities. Having resigned as solicitor-general, on 20 April 1536 he was appointed surveyor of liveries, and four days later was named chancellor of the newly erected court of augmentations, charged with overseeing the dissolution of the monasteries, a task for which he showed a particular relish and acquisitiveness that has contributed to the tarnishing of his posthumous reputation.' (10)

In April 1536, Richard Rich, Thomas Cromwell and Thomas Audley were given the task of investigating claims made against Queen Anne Boleyn. (11) This included interviewing Mark Smeaton, Henry Norris, Sir Francis Weston, William Brereton and George Boleyn. It has been suggested that Rich might have tortured Smeaton in order to get a confession. This information was used to gain a conviction and execution of the Queen and her five suggested lovers.

Rich was a protégé of Thomas Cromwell, but he hastily abandoned his patron when he was arrested on 10th June, 1540. (12) Cromwell was charged with treason and heresy and Rich willingly provided damaging testimony against him. On 28th July, Cromwell walked out onto Tower Green for his execution. In his speech from the scaffold he denied that he had aided heretics, but acknowledged the judgment of the law. The executioner bungled his work, and took two strokes to sever the neck of Cromwell. He suffered a particularly gruesome execution before what was left of his head was set upon a pike on London Bridge. (13)

Rich was rewarded by being made a Privy Councillor in August 1540. Over the next few years he achieved great success as chancellor of the court of augmentations (the largest of the royal revenue courts). As P. R. N. Carter has pointed out: 'The possibilities of such an office were great, and Rich managed to amass a considerable landed estate in Essex, centred on Leighs Priory (a gift from the king in 1536), which he enlarged. The temptations it presented were equally great, however, and several times Rich was called to clear himself of accusations of corruption, as in April 1541 when John Hillary alleged (unsuccessfully) that Rich had defrauded the crown.' (14)

Catherine Howard Investigation

On 2nd November, 1541, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, presented a written statement of the allegations against Queen Catherine Howard to Henry VIII. Cranmer wrote that Catherine had been accused by Mary Hall of 'dissolute living before her marriage with Francis Dereham, and that was not secret, but many knew it.' (15) Henry reacted with disbelief and told Cranmer that he did not think there was any foundation in these malicious accusations; nevertheless, Cranmer was to investigate the matter more thoroughly. 'You are not to desist until you have got to the bottom of the pot.'

Richard Rich and Sir John Gage were given the task of questioning Thomas Culpeper, Francis Dereham and Henry Manox. According to Alison Weir, the author of The Six Wives of Henry VIII (2007) Rich and Gage 'had supervised the torturing, with instructions to proceed to the execution of the prisoners, if they felt that no more was to be gained from them by further interrogation.' (16)

In February 1546 conservatives in the Church of England, led by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, and Edmund Bonner, bishop of London, began plotting to destroy the radical Protestants. (17) They gained the support of Henry VIII. As Alison Weir has pointed out: 'Henry himself had never approved of Lutheranism. In spite of all he had done to reform the church of England, he was still Catholic in his ways and determined for the present to keep England that way. Protestant heresies would not be tolerated, and he would make that very clear to his subjects.' (18) In May 1546 Henry gave permission for twenty-three people suspected of heresy to be arrested.

Richard Rich took part in this prosecution of heretics. One of those arrested was Anne Askew. Bishop Gardiner instructed Sir Anthony Kingston, the Constable of the Tower of London, to torture Askew in an attempt to force her to name Queen Catherine Parr and other leading Protestants as heretics. Kingston complained about having to torture a woman (it was in fact illegal to torture a woman at the time) and Richard Rich and Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley took over operating the rack.

Despite suffering a long period on the rack, Askew refused to name those who shared her religious views. According to Askew: 'Then they did put me on the rack, because I confessed no ladies or gentlemen, to be of my opinion... the Lord Chancellor and Master Rich took pains to rack me with their own hands, till I was nearly dead. I fainted... and then they recovered me again. After that I sat two long hours arguing with the Lord Chancellor, upon the bare floor... With many flattering words, he tried to persuade me to leave my opinion... I said that I would rather die than break my faith.' (19) Afterwards, Anne's broken body was laid on the bare floor, and Wriothesley sat there for two hours longer, questioning her about her heresy and her suspected involvement with the royal household. (20)

Despite conservative religious sympathies, Rich consolidated his position by keeping on good terms with Edward Seymour and Thomas Seymour, and by collaborating in the destruction of the conservative Thomas Howard, fourth duke of Norfolk, and his son Henry Howard, earl of Surrey, in the months before the death on Henry VIII on 28th January 1547. He held the post of Lord Chancellor until January 1552.

Sir Richard Richardson

Rich and his wife entertained Queen Mary on her progress to the capital early in August 1553, and was named a Privy Councillor on 28th August. Having profited greatly from the dissolution of the monasteries, Rich was forced by Mary to restore some properties. He took part in the persecution of Protestants and was involved in the burning of Thomas Watts, in June 1555, after he refused to attend Mass. (21) According to P. R. N. Carter 'it seems clear that Rich remained a conservative in religion throughout his life, and his earlier endorsement of reform was motivated more by politics and greed than by personal faith'. (22)

Richard 1st Of England

Richard Rich supported the restoration of the royal supremacy under Queen Elizabeth, but his Catholic faith prompted him to vote against the Act of Uniformity in 1559. Although he was excluded from the privy council, he was not imprisoned. He died at Rochford on 12th June, 1567.